Recommended book about the connection of racism and yoga: Gail Parker, Restorative Yoga for Ethnic and Race-Based Stress and Trauma, London and Philadelphia 2020. (Click here for the German version of this article)

The recently published study by psychologist and yoga therapist Dr Gail Parker from the USA is one of the publications that I, and I think many other readers, have been waiting for.

Perhaps without really knowing it, because – to say it in advance – Gail Parker presents a groundbreaking study.

In it, she introduces readers affected by racism, therapists, anti-racism activists, yoga teachers and many others, perhaps for the first time, to terms, examples and ways of dealing with experiences and their consequences that most of us have had, but which have rarely been the subject of conscious discussion.

The starting point of Restorative Yoga for Ethnic and Race-Based Stress and Trauma is the author’s observation that in a racist world, each of us carries emotional wounds based on events of stress and trauma related to ethnicity and racism that are unacknowledged and therefore unhealed.

As a psychotherapist, Gail Parker has spent decades studying this specific form of stress and trauma. In this dense and highly readable account, she expertly weaves together findings and theories from psychology, behavioural research and yoga philosophy with short anecdotes, fables and the extensive experiential knowledge of her almost fifty years of yoga practice.

Before we look at the content of the book, let us first make a brief digression to clarify the concept of race as it is used by Gail Parker in the US context.

RACE vs. „RASSE“ — Lost in Translation

If you are unfamiliar with the use of the term “race” in the United States and the debates that have taken place there, reading this word may make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up (especially if you are a German-speaking reader). But the uses and meanings of “race” are by no means congruent with “ethnicity”.

As a result of critical debates about the crimes and ideology of the Nazi dictatorship in Germany, the assumption that humanity could be divided into different ‘races’ was deconstructed as biologistic, inaccurate and dangerous. With this deconstruction of the concept at the heart of Nazi ideology, the use of the term “race” almost completely disappeared from German public discourse. When it is mentioned, as it is in this article, we often put quotation marks around it to express our distance from this construction.

Nevertheless, the concept and the term persist in private, right-wing political and right-wing spaces in Germany, and we therefore use the term racism accurately to describe these ways of thinking and acting. And in Germany, too, there is currently a renewed debate about the use of ‘race’.

In the US, the concept of race continues to be the subject of much debate, and therefore its use is not universal or uniform. Since the 1970s, scholars and activists have treated race as a product of social construction within Critical Race Theory (CRT). At the same time, the concept of race is often self-attributed, for example in government information, censuses or surveys.

In the US context, as in Germany, it is necessary to look more closely at who uses the term, how and when. For example, biologists and geneticists often refer to a biological concept of race, whereas social scientists and anti-racist activists, for example, use the term in the sense of the CRT, primarily in its social dimension. Throughout the history of slavery and immigration in the US, the concept of race has also been deeply linked to struggles against social injustice and racial discrimination.

This brief digression is an example of the translation work that Gail Parker’s study requires of international readers. We have to translate not only the language, but also some aspects of her concepts and some of her examples. But it is also these necessary translations that contribute to the formation of an anti-racist and truly yogic attitude and thus to the healing of us all.

Are you ready to get to work?

In her foreword, Gail Parker urges with clear urgency how overdue it is to look more closely at our own wounds in the wake of racism and commit to healing them.

In eight clearly structured chapters, the author unfolds a sensitive and informative guide to help each of us on the necessary path of inner and personal healing. And those of us who are therapists or yoga teachers, for example, who wish to help others on their path to greater healing, will find in Gail Parker’s book the necessary background knowledge, important anecdotal evidence, study results and many practical tips for designing an appropriate yoga practice. At the end of each chapter there are suggested questions for discussion and reflection, instructions for writing reflections and further reading.

Gail Parker explicitly invites all readers onto the path of this inner work. Regardless of our cultural, ethnic or national background, we all experience the effects of racism: from the stress and trauma of everyday racial violations, microaggressions, helplessly witnessing racist events, to white fragility (DiAngelo 2011) – a state in which even minimal racial stress is perceived as unbearable and triggers a range of defence strategies.

Parker’s study helps us enormously to embark on a journey of critical self-reflection and to become more aware of our own blind spots when it comes to culture, ethnicity and privilege.

What are the specific characteristics of trauma related to racism?

Even more prevalent today than the ethnic and racist traumas Parker describes is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Based on her clinical experience, Parker believes that large parts of US society are affected by diagnosed and undiagnosed PTSD. She points to the links between war and flight and judges:

„As a society, we are unaware of our unresolved trauma and its effects, including the effects of the unhealed wounds of ethnic and race-based stress and trauma. We are traumatized physiologically and emotionally.”

But a central concern of the study is also to highlight the differences between race-based traumatic stress injury (RBTSI) and PTSD. Although the symptoms of RBTSI can be of a similar physiological nature, RBTSI differs primarily in the following characteristics:

different contexts in which these specific injuries occur

psychological and emotional consequences

theoretical approaches to stress and trauma

- different contexts in which these specific injuries occur

- psychological and emotional consequences

- theoretical approaches to stress and trauma

According to the author, racial traumatic stress is a specific traumatic experience that occurs in the context of negative and emotionally painful experiences of racial discrimination.

Racial stress builds up cumulatively and in many cases leads to chronic symptoms due to the lack of healing periods before the next experience. Among the many signs, Parker lists defensiveness, anxiety, depression, anger, sleep disturbances, flashbacks, low self-esteem, shame and sometimes guilt.

In the very first chapter, Gail Parker introduces ancestral memory with references to the work of Joy DeGruy and Resmaa Menakem. Here Gail Parker offers us a concept that is particularly applicable to Europe and other parts of the world scarred by world wars and civil wars. Traumatic patterns rooted in the past do not exclude anyone in the present.

Breaking yoga’s silence on racism

Gail Parker speaks out against the frequent silencing of racism in yoga and with her study makes a significant contribution to initiating a debate about racism in the fields of yoga therapy and trauma-informed yoga. She believes this is necessary in the context of increasingly diverse yoga communities.

As readers, we learn in the first chapter that every yoga class carries risks of stress and trauma in the context of ethnicity and racism. Here Parker develops important arguments, based on her own racist experiences, for a critical awareness of ethnicity and racism among yoga teachers, practitioners and therapists. As she clearly shows, we run the risk of hurting others through our neglect, attitudes, actions or language as long as we lack this awareness.

Parker devotes a very inspiring chapter to the influence of spiritual activism on healing in the context of racism. She discusses spirituality in the context of political and social change, and the activist and yogic arguments she makes are compelling. Gail Parker shows us in a practical way how we can work for improvement while caring for our own health. This is an extremely important chapter for those who are involved in issues close to their hearts and who sometimes tend to overlook their own needs.

Restorative yoga for nurturing the soul

„As yogis, we have amazing tools that we can use to address ethnic and racial wounding and help the world become a better place for everyone.”

Gail Parker emphasizes in this quote that we as yogis have amazing tools to heal the wounds caused by racism and to help make the world a better place for all.

Experiences of trauma and stress not only leave traces in our thoughts and feelings, but also end up in our bodies through the nervous system. As a result of various symptoms and coping strategies of trauma, many people experience a disconnection of body, mind, heart, and spirit with unhealthy consequences. If we ignore the physical symptoms of stress and trauma, we run the risk that they will manifest as seemingly unrelated physical illnesses or emotional disorders.

In her book, Gail Parker teaches us how to use yoga philosophy and the practice of asanas (physical exercises) and meditation to counteract this disconnection, reconnect more sensitively with ourselves, and invite more harmony into our lives. When body, mind, heart, and spirit are in harmony, we act with clarity and wisdom without being overwhelmed by triggered emotions.

Against the backdrop of her profound unfolding of the Kleshas, Parker argues that we can find our true nature particularly well through the comparatively quiet and motionless practice of Restorative Yoga. The contemplative nature of the practice teaches us that there is a higher state of consciousness beyond the boundaries of our egos that can guide, inform, and protect us.

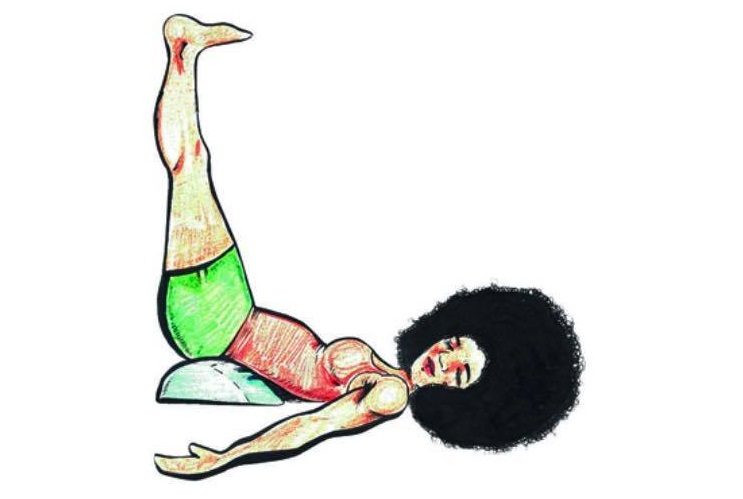

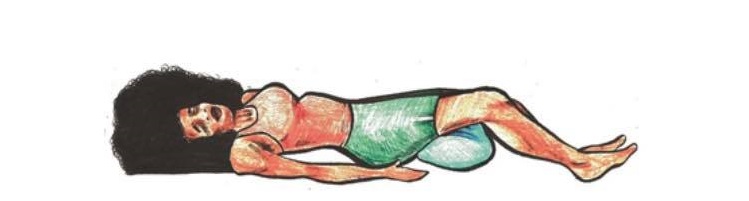

In Restorative Yoga, we use many tools, from blankets and blocks to pillows, chairs, bolsters, walls, and eye pillows. These tools minimize muscular effort as much as possible and support the body in each pose so that we feel physically comfortable and slip into a deep state of relaxation without falling asleep.

Because of the length of time we stay in the supported postures, the effects reach deep into our nervous system, strengthening the body’s own mechanisms for self-regulation. With consistent practice, Parker says, we can release chronic patterns of tension and achieve emotional balance by balancing body, mind and emotions.

Gail Parker concludes her remarkable study with a practical chapter. Here we find clear instructions for meditation and breathing exercises, as well as detailed descriptions of recommended postures.

Thank you for sharing . Nice article , I will definitely read more about it in the book

Great! Thank you for this feedback! This book should be read in all Yoga TTC‘s and by anyone who is interested in Yoga in a broader context.